Lilywatch Part3: Computers and Code

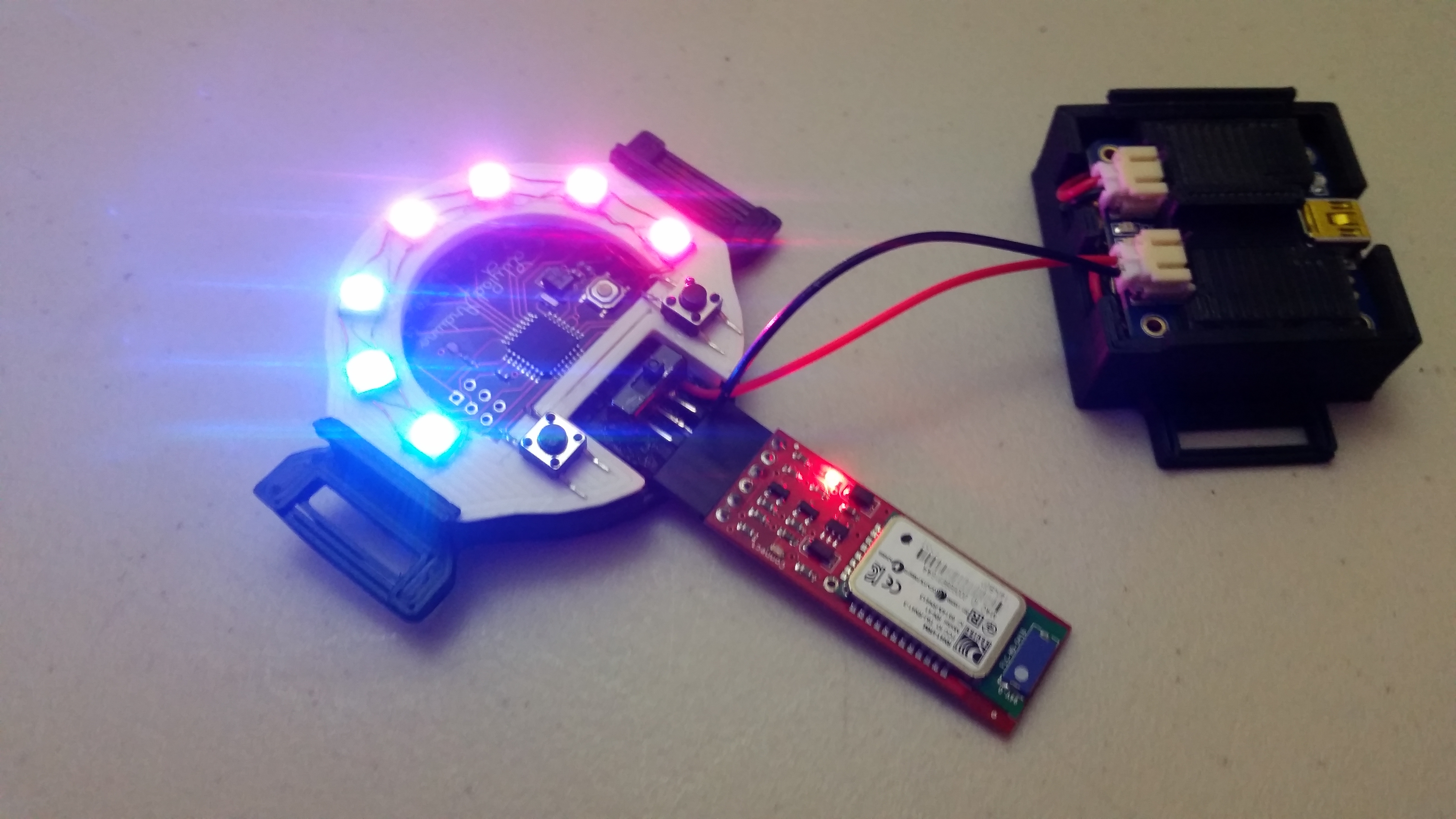

This is a continuation of my previous posts regarding the Lilywatch: A watch built using an Arduino. This post goes over the programming and computer aspects of the device.

Computers and Code

Arduino

I call myself primarily a programmer, so this part of the project was the least daunting. However, I have never done anything so big with an Arduino before. I wish I had learned earlier that I could use multiple files, that would have made things a lot easier. Navigating a single 900-line file is infuriating to say the least. But the job got done, all was well, and I finally had a wearable, functional watch made from an Arduino.

I also put the code on GitHub. At first it seemed kinda silly since it was all in one file, but versioning software is still useful even then. I just had a very sad looking repo. TODO ADD LINK

Significantly later on in the project, I did end up doing a major refactor and splitting all the different modules into their own classes.

Arduino was mostly OK with this, however I had to use Notepad++ as the actual editor since Arduino’s IDE mandated that all the files open in scrolling tabs which was unbearable. Arduino’s compiler also didn’t seem to like having sub-directories which made me sad, but I managed all the same.

The only real concern I started having was that splitting the files seemed to take up noticeably more memory on the board when uploading. I was at a little more than 50% before the split, and about 70% after. So at least I still had some room, but I had to make sure I considered that whenever I thought about adding more features. Future things were going to have to do the thinking outside the board.

Anyway, the code is structured in such a way so that each “app” or state is its own class and stored in an array in the Lilywatch class. The Lilywatch class is the main overseer of everything, looping through whichever state is the current one and storing references to all the sensors. I also made a class called a daemon. A daemon is typically a program or process that runs in the background. Since Arduino doesn’t have multi-threading, these daemons were just like states but they were always running. Daemons handled things like changing the brightness based on light levels or handling input from bluetooth. In comparison states were things like the clock or flashlight states, which were only run while selected.

Android

To enable communications between the watch and my phone, I had to write some sort of app to relay information to Tasker, which I would then use as the main brains behind the watch/phone communications. I did this because 1) I liked the idea of being able to edit things on the fly, without having to return to my computer to reprogram a feature and 2) I am not greatly skilled in Android programming yet. I’ve been experimenting for a while, but nothing has come out that I’m proud of.

So the basic plan was: - Obtain a bluetooth connection using my own Android app - Pass any incoming messages from the watch to Tasker using that app

The App

The app was as simple as I could make it. I compiled what I needed from Google’s bluetooth examples and BlueTerm which was open source.

It wasn’t anything pretty to look at, in fact it still just looks like Google’s example, but it worked. All it did was establish a connection to the phone and send out / receive intents pertaining to anything related to that bluetooth connection. To put it simply, intents are Android’s way of sending messages between its various components. I was going to use these to tell Tasker when new messages from the watch were received and I made Tasker send Intents to my app which detailed messages to send over bluetooth.

Tasker

If you don’t know what Tasker is, it is an app that listens to events that happen on your phone and allow you to designate actions to be performed when those events happen. For example, make a popup whenever the clock strikes 12 or vibrate to a pattern when you get a text from a certain person while in a certain location. It has a lot of possibilities. So I made it listen to intents broadcast from my small app and make sent return intents accordingly.

Getting this working was as fun as it was frustrating. This was my first major delve into the mechanics of Tasker, so getting used to the interface was unpleasant, but the results were worth it. Whenever a bluetooth connection to the Lilywatch was reported, Tasker would send a message detailing the current time so that the watch could stay accurate. I also programmed events in using the Notification Listener plugin so that whenever a notification arrived using the from hangouts(SMS), Google(Reminders), or an alarm went active, Tasker would send corresponding messages to the watch so it can notify me.

Experiments

Bluetooth and RSSI

During early testing with the bluetooth module, I wanted to see if there was a way to recreate a program I had in middle-school that unlocked my computer automatically when my phone was in range. I did some research and discovered this was done by reading a bluetooth connection signal strength to estimate a distance. It was far from accurate, but it could at least tell if I was a few feet vs in another room.

Bluetooth uses something named RSSI or Received Signal Strength Indication to inform the bluetooth radio’s user of its connection strength. However, I was met with some major problems when trying to use this for anything practical.

My intention was to use it as a sort of ‘find my phone’ application, beeping like a metal detector whenever you got nearer. Unfortunately, the only way to get RSSI information was to request that they start being broadcast from the radio module’s command state itself. The worst part was that they would only ever update every 5 seconds, and it would be nigh-unpredictable. The signal strength would jump from full power down to ~80% at around 10m, then gradually fell sporadically until something blocked line-of-sight with the device.

I tried turning down the power consumption of the radio module, but it showed the same effect of not doing anything for a distance and then gradually falling although this time the initial distance was about 2m. Still, not that great. It could be usable if the strength gradient it took was more predictable, but it jumped around far too much. Plus, if anything broke line-of-sight at the lower power setting, it would just disconnect entirely.

I still see potential to get this feature working, and maybe one day find to achieve it, but for now I am putting it on hold. I did however keep the power level low for the sake of battery consumption.

Unity

In my attempts to make an interactive app, I also tried communicating with a Unity3D project on my PC over serial. Getting it to work wasn’t hard at all, since C# already has classes built in for serial communications, the only fault was that I couldn’t calculate a decent orientation vector given the accelerometer and magnetometer data. For whatever reason, the compass seemed so inconsistent, and whenever I pointed in certain directions, the orientation vector was horribly skewed. I wanted to get some sort of mock-motion control going, but I scraped that idea quickly in favor of working with the TV. Which I will talk about in the next post.

A note to those who may wish to use Unity3D, it required enabling .Net 2.0, which you can do by going to:

ProjectSettings > Player settings > Change .Net 2.0 Subset to .Net 2.0